IUL illustrations: That was then; this is now

My July 2013 feature article for InsuranceNewsNet Magazine, “Illustrated Promises; Unmet Expectations,” addressed a problem in which insurance regulations that were approved in the mid-1990s were resulting in illustration outcomes that were unlikely to occur and likely to cause disappointment. Further, policy illustrations continued to be used to project future values, a purpose regulators and the Society of Actuaries had long refuted.

By 2013, policy illustrations were again coming under regulatory scrutiny as the National Association of Insurance Commissioners was beginning to address indexed universal life, a relatively new product that was quickly becoming a best-seller among the different forms of universal life insurance. IUL was a very different variation of UL that hadn’t even existed when the current illustration regulation was finalized in 1995. When nonguaranteed bonuses were included, illustration net crediting rates of 8% or 9% were not uncommon — deployed as constant (but nonguaranteed) accumulation assumptions over many decades.

IUL is the most recent generation of UL insurance products to come along since UL was introduced in 1978. Variable universal life — a security — became popular in the late 1980s, and then along came guaranteed universal life during the latter part of the 1990s. Right on time for the decennary evolution of UL products, IUL began to gain traction in the recovery from the Great Recession. IUL intends to be a non-

security blend of earlier iterations of UL and VUL, with all the advantages of flexible premiums and none of the potential disadvantages of volatile subaccount values that could produce negative forces on cash value accumulation.

What makes IUL both attractive and challenging to illustrate is that there is no “earned interest rate underlying the disciplined current scale” to serve as a maximum (but also persistent) projection rate when producing an IUL illustration. IUL defies conventional wisdom when it comes to developing an appropriate policy illustration rate, especially when following the Goldilocks Rule — not too high, not too low, but just right.

Consider the following recent situations involving complex life insurance products, compounded by aggressive recommendations for implementation.

1. IUL and premium financing for retirement income

Fifty-seven-year-old Victor K’s long-time trusted financial planner had an important idea to share with him: a wealth generation plan. And it was such a valuable planning concept that the planner went ahead and initiated a similar plan for himself. The essence of the presentation — primarily drawn from a policy illustration — included:

» Apply for an IUL policy in the amount of $5 million.

» Use a 1035 exchange of an existing $1 million par whole life policy with $300,000 of surrender value plus pay premiums of $320,000 a year for 10 years, but arrange premium financing to pay all those premiums.

» In Year 11, repay the $3.5 million bank-financed premium loan (and accumulated interest) out of policy cash values.

» Sit back and collect $200,000 a year of tax-free income for the rest of his life beginning at age 70 — with policy withdrawals and loans as far as age 120, or however long he lived.

» He would still have $4.5 million of net death benefit at an average life expectancy (89) or $70 million if he lived to 120.

But in fact, assuming the policy can redeem the third-party premium financing (and replace it with an internal policy loan), there was less than a 50% probability the plan would be viable after even the first retirement cash flow. There was less than a 10% probability of success well before average life expectancy.

2. IUL for retirement income

Seventy-year-old physician Gregory J’s new financial planner suggested Greg use his professional practice’s profit-sharing plan to buy a $5 million IUL policy and then sell the policy 10 years later from the profit-sharing plan to Greg’s irrevocable life insurance trust.

» A total of $2 million in premiums was to be paid by the retirement plan, prefunding all future premiums and illustrating $100,000 annual tax-free income beginning at age 65 — with policy withdrawals and loans for as long as his wife lived, up to age 100 — under a spousal withdrawal provision of the ILIT.

» However, the client funded only $1.5 million of the intended funding, and the agent neglected to drop the death benefit from $6.5 million to $1.5 million in Year 8 as originally illustrated.

As a result, there was only a 27% probability the plan would be viable to age 100.

3. IUL and premium financing for retirement income

Fifty-two-year-old physician Jennifer R. had a $3 million 20-pay whole life policy with a $110,000 annual premium that began to strain Jennifer’s budget.

» She asked her long-time insurance agent (who sold the original policy) to see if she could reduce her premium obligation. He responded with a proposal to exchange the whole life’s $500,000 cash value for a premium-financed IUL policy illustrating $260,000 annual tax-free income beginning at age 65 — with policy withdrawals and loans as long as she lived, up to age 100.

But in fact, when we reduced the long-term cap expectation to 7% from 9% to expand on that possibility, the first failure occurred at age 84, and there was a 91% probability the plan would not be viable to age 100.

What do these insurance cases have in common?

For at least the past 10 years, high-end life insurance sales have been less about protecting a family, business or charity from financial loss due to the insured’s premature death, and more about accumulating large amounts of cash values from which to withdraw and borrow substantial income tax-free cash flow from the policy at and during retirement.

For an even longer period of time, high net worth individuals have been encouraged to borrow the substantial upfront premiums with which to fund those so-called retirement benefits. At the same time, lenders have steadily reduced their minimum personal financial criteria for making such policy loans. Placing large life insurance policies into retirement plans is another form of premium financing.

We still hear the rallying cry supporting IUL: “Zero is your hero!” Except it isn’t. IUL policies have some attractive long-term attributes for the right type of buyer, but the policy illustration misleads sellers and buyers into believing cash value accumulation occurs with a constant rate of return. It does not. Cash value at the end of a segment year can be less than it was the prior year, depending on the charge side of the ledger.

To be fair, in the cases I cited earlier, there was no evidence the licensed agent intended to defraud the client. But these cases highlight negligence in using a policy illustration as the exclusive means of understanding — and selling — a concept that ultimately caused great harm and financial loss to the client and likely to the advisors. All three of these life insurance cases are currently being litigated.

The primary reason market-based policies fail to deliver on illustrated promises is that the dollar sequence of return risk cannot be evaluated with the tools currently made available to agents and their clients. But appropriate tools do exist. As a form of statistical analysis, Monte Carlo assessment can provide an understanding of the degree to which policy illustrations continue to fail expectations.

What is Monte Carlo?

Assuming an otherwise identical set of illustration details such as an assumed premium, death benefit, age/gender/class, etc., Monte Carlo analysis applies 1,000 or more unique randomization scenarios to the buyer’s assumed asset allocation/index of choice (i.e., the methodology by which the policy accumulates long-term value). Of course, over the life of the insured, policy credits must exceed policy debits for the policy to sustain and become a death benefit. As a result of this randomization process, Monte Carlo analysis estimates the probability of success among those many scenarios of returns for the buyer to access entirely new insights into the policy being reviewed.

Life insurance companies have long used Monte Carlo to estimate their long-term profits in a number of design scenarios for new policies, but agents have been on their own in using similar technology with their prospects and clients.

Monte Carlo analysis, when properly applied, is the only method to form an unbiased outcome expectation that cannot be manipulated.

The question for the client that makes this process so useful is “What is your minimum acceptable probability of success?” Most prospects will indicate something between 80% and 90%; after all, it is life insurance! By the way, if a potential buyer’s minimum threshold is 100% certainty, they probably should look at a policy style with more underlying guarantees!

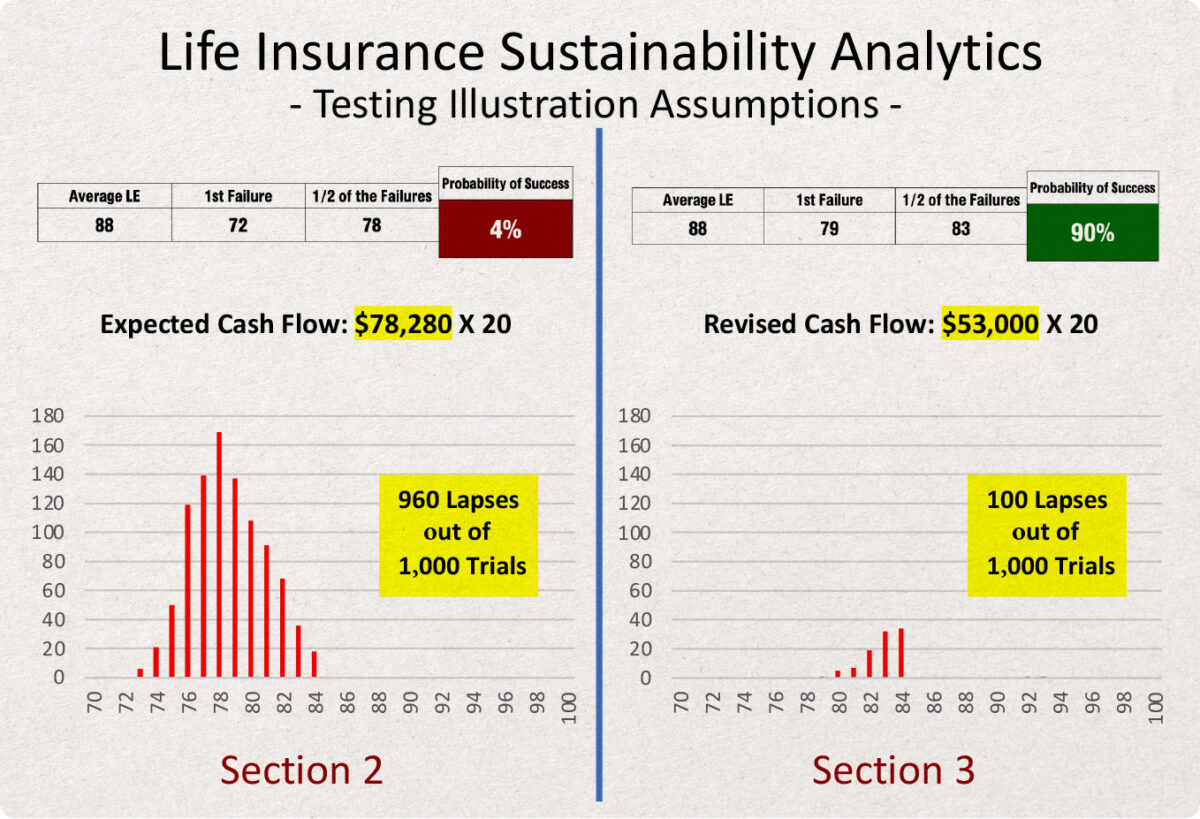

Section 1 is a typical summary of an actual, current sales illustration: paying a premium of $25,000 a year for 20 years, and the following year expecting to withdraw and borrow $78,280 for another 20 years. To put it more simply, that’s a total of $500,000 into the policy and $1,565,600 out of the policy, for an ostensible long-term 6% after-tax equivalent rate of return (since there is no tax) on premiums and cash flows, plus an illustrated net death benefit of $243,000 at age 89 (average life expectancy).

That’s a very attractive projected outcome. Unfortunately, it’s predicated on the assumption of a constant 6.3% (illustrated) crediting rate every year for the next 76 years. Since that is not a realistic assumption (neither in the magnitude of the return nor in its expected duration) it is much more useful to instead determine the probability of successfully achieving these premiums, withdrawal and ultimate death benefit results — using an asset allocation similar to the chosen index — with its guaranteed floor of 0% and current cap.

As can be seen in Section 2, a Monte Carlo analysis using the prospect’s asset allocation mapped to an appropriate index suggests there is only a 4% probability the plan can successfully pay out the expected payments of $78,280 from ages 65 through 84 and maintain the policy until death. In fact, only 40 of the 1,000 hypothetical variations in this analysis sustain to age 100. The overwhelming number of hypothetical observations will lapse prior even to average life expectancy, with half of all anticipated failures occurring by illustration age 78.

Four percent is a pretty low likelihood with its 960 projected failures out of 1,000 hypothetical trials between now and age 84 — and we assume it would undoubtedly be unacceptable if the client had this information.

Nonetheless, the other part of the process must seek the prospect’s response to the question “What’s your minimum acceptable probability of success for this purchase of insurance?”

Assuming the prospect comes up with the typical 90% response, we can provide a reasonable expectation for this proposal in Section 3: There is currently a very high probability the prospect can count on cash flow at retirement in the amount of approximately $53,000 per year for 20 years for a projected after-tax return of 4.5%. Periodic reassessment should warn of any failure possibilities well in advance.

What is your standard of care obligation?

Licensed insurance agents have among the lowest state-imposed obligations to standards of care in the financial services industry. By contrast, approximately 14,800 Registered Investment Advisory firms and their more than 350,000 investment advisory representatives have statutory-imposed fiduciary duties to their clients. Fiduciary duties to their clients are membership-imposed on 100,000 CFP professionals, while 640,000 registered representatives (this number includes an overlap with IARs) have a standard of obligation to their broker-dealers and are bound to the equal care obligations of Reg-BI.

In addition to their obligations under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act, the Department of Labor is considering a rule requiring licensed insurance agents to act as fiduciaries when selling annuities to IRAs. And, finally, about 20,500 New York State insurance agents selling life and annuity products to residents of New York are now required under New York’s Regulation 187 to work only in the client’s best interest and to make only recommendations that are suitable to their prospective clients.

By and large, licensed agents in the other 49 states are not required to act with higher standards of care due to legislation, regulation or membership.

Research from Stanford Law Review looked at the career paths of former registered representatives who, because of their own actions and penalties from the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, were no longer allowed to sell securities. Where did those reps go? They mostly went into the life insurance business. Why? Because they could, with much easier qualifying exams and substantially lower standards of care.

It is unclear whether the higher standard of care applicable to, for example, an IAR or a registered representative does or does not automatically carry over as a duty to activities additionally pursued with a client as a licensed insurance agent. We know the duty is all-inclusive as it applies to CFP professionals in the process of providing financial advice. And by definition, the duty applies to insurance activities with New York residents regardless of an advisor’s other credentials or designations.

The extent of that duty is not yet resolved. For example, a California agent who is also an IAR providing financial advice and investment services and life insurance products to a client either 1) has no elevated duty on the life insurance portion of their insurance work, because California does not impose a best interest/suitability rule for life insurance on its licensed insurance agents, or 2) does have such a duty because their overall client obligations as an IAR or a registered representative supersede the lower state-imposed insurance standard.

When the law is not clear — or it is ambiguous or different between states — beware of unintended consequences. In the most extreme example, it’s up to a jury to decide!

Alternatively …

I suggest financial advisors assume they will be held to the highest duty applicable to their various designations and licensure, and provide advice and ongoing management to their clients as appropriate to the various products — including insurance — they have chosen to represent.

The way most of us were trained to sell insurance products was to become knowledgeable and share our expertise with the client, implying that because of our knowledge and experience, we can tell you what’s in your best interest.

But it can’t work that way any longer. Best interest standards do not mean imposing on clients what we think is in their best interest. Subsequent disappointment can lead to client harm and then lawsuits. The evolving standard of care is to make certain that clients have the opportunity to choose products they perceive are suitable to their circumstances and are in their best interest, and best practices suggest providing written recommendations to help them along the way (protecting ourselves later on).

Securities, banking, retirement planning and financial advice are largely regulated at the federal level. However, consider the vast difference in the required client standard of care for licensed agents between New York and California in the sale of life insurance. Standard of care regulation at the state level leaves even the most professional life insurance agents wondering how to meet their cross-state obligations. But the high standard is not impossible, nor does it have to be onerous. It just takes a commitment to focus on the client with skill, diligence, prudence, knowledge and client loyalty.

I am always reminded of the professional pledge of the Society of Financial Service Professionals:

“In all my professional relationships, I pledge myself to the following rule of ethical conduct: I shall, in the light of all conditions surrounding those I serve, which I shall make every conscientious effort to ascertain and understand, render that service which, in the same circumstances, I would apply to myself.”

Richard M. Weber, MBA, CLU, AEP (Distinguished), is a 57-year veteran of the life insurance industry, having been a successful agent, a home office executive, a software designer, author of four books and more than 400 published articles, and an educator. He is the co-creator of Certified Insurance Fiduciary, an online program for advisors wanting to enhance the scope of their advisory services. He may be contacted at richard.weber@innfeedback.com.